International consortium seeks development of new drugs for neglected diseases and malaria

Research and development of new drugs against neglected diseases and malaria will have investment of R$ 43,5 million. The purpose of the consortium is to identify preclinical candidates likely to become new drugs for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis, Chagas disease and malaria

09/12/2019

Between 2012 and 2018, only 3,1% of new drugs that hit the market were focused on diseases such as malaria, leishmaniasis and tuberculosis

Tropical diseases date back to the colonial period, when European sailors made their expeditions to so-called New World and encountered a series of parasitic diseases that spread rapidly due to the high temperatures and humidity of those regions. More than five centuries later, tropical diseases remain a global health challenge. The scarcity of safe, effective and affordable treatments, accentuated by the historical invisibility of these diseases to the pharmaceutical industry, ultimately lead hundreds of thousands of people to death each year in many poor or developing countries.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) elected 17 tropical pathologies as priorities. Although they differ from the point of view of contagion, they all have two crucial points in common: they are caused by infectious agents and mainly affect people living in poverty and vulnerability. The list of neglected diseases (NTDs) today comprises 21 diseases, including Chagas disease and leishmaniasis. In Brazil, data on inequality have led the Ministry of Health to add malaria and tuberculosis to the group since 2008.

The few drugs available for these diseases are expensive, have low efficacy and/or have undesirable side effects. Trying to change this reality, in late November, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) and the State University of Campinas (Unicamp), together with the University of São Paulo (USP), the international organization Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) and the São Paulo State Research Support Foundation (Fapesp) have signed an agreement to create a global collaboration network for research on new drugs for Chagas disease, leishmaniasis and malaria. The idea of the project is to stimulate the development of capacities for research of new drugs in Brazil through the exchange of the best knowledge practices.

Supported by Fapesps Technological Innovation Partnership Research Support Program (PITE), the international consortium will receive investments of R$ 43,5 million over the next five years. The funding will be shared between the Foundation itself (R$ 7.8 million), DNDi and MMV (R$ 12.8 million), as well as Unicamp and USP (R$ 22.9 million).

“The great advantage of this consortium is the creation of an international multidisciplinary network, based on the excellence models from the major global research institutes, but which is oriented to the needs of the populations of endemic countries. It is a joint effort for the same purpose: to obtain safe and effective treatments for Chagas disease, leishmaniasis and malaria, summarized Jadel Müller Kratz, DNDi Research & Development Manager. According to him, this is an important milestone to science for the discovery of new antiparasitic agents, as it brings together Fapesp, two of the leading Brazilian universities and non-profit organizations whose mission is to deliver new therapeutic alternatives to fight parasitic diseases. “Collaboration between research groups and the exchange between Brazilian and foreign researchers is an important aspect of the partnership. The internationalization of Brazilian science is fundamental”, he added. The goal of DNDi is to deliver a preclinical compound that may, after further testing, become a new treatment for Chagas and visceral leishmaniasis.

MMVs work will involve the creation of a single-dose oral drug against malaria. According to the entitys scientific director, Timothy Wells, the discovery of new drugs will allow endemic countries like Brazil to eliminate the disease from within its borders and also support global eradication. “We are delighted to be able to draw on the expertise of Brazilian scientists at Unicamp and USP and combine them with MMVs malaria experience to develop antimalarial drugs for the Brazilian population and other countries”, he said.

Luiz Carlos Dias, professor at the Unicamp Chemistry Institute, in charge of the overall coordination of the project, stressed that this partnership will certainly pave the way for future collaborations, promote interactions between scientists with different knowledge of Brazil and abroad and trigger the nucleation of Human Resources in the field of drug discovery. It will certainly open the door to new ideas for entrepreneurship and technological innovation in the state of São Paulo, as well as putting Brazilian scientists on the select world list of translational science trained researchers, he said. Still according to him, the consortium will lead to the consolidation of a global partnership model that contributes to innovation, the advancement of knowledge in the field of the discovery of new drugs for tropical parasitic diseases, the acceleration of research schedules and the sharing of data.

R&D Process

The drug research and development process is complex, long and requires strong long-term investment. When it comes to discovering new molecules, according to Charles Mowbray, Drug Discovery Director at DNDi, it is very important to have a clear vision of what you want to develop. The Target Product Profile (TPP) describes the characteristics that the drug needs to have to be appropriate for the patients we need to treat, he explained.

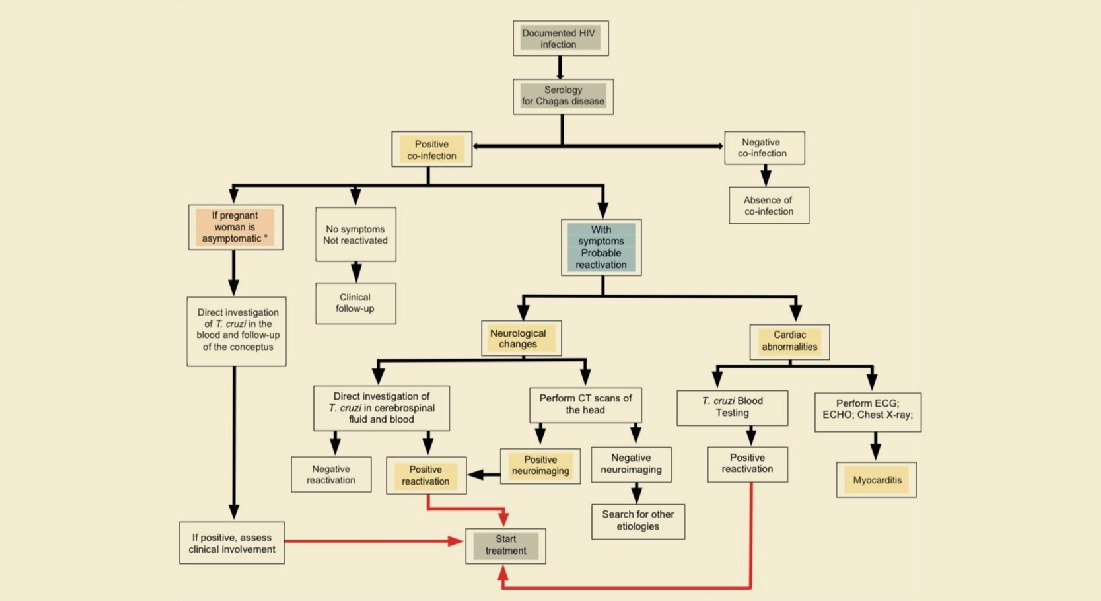

After this definition, the first step is the identification and validation of active compounds (hits) originating from compound libraries. Once a new chemical series has been identified, it undergoes cyclical multiparametric optimization processes (pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety). Optimization follows the criteria defined in the target product profiles until a preclinical candidate with acceptable efficacy and safety characteristics is obtained, or the chemical series abandoned.

The potential drug should then proceed to preclinical laboratory (in vitro) and animal (in vivo) testing to determine whether it is safe to be tested in humans. The research dossier is presented to regulatory bodies and research ethics committees that validate whether the new drug can be tested on people.

The next step is human clinical trials.

• Phase I – initial small group safety trial of healthy volunteers to define the highest possible dose tolerated by humans and their pharmacokinetic profile;

• Phase II – safety and efficacy test in a small number of patients with the disease, to verify if the drug is indeed effective and to define its therapeutic regimen (frequency, dosage);

• Phase III – Usually with the defined dose and therapeutic regimen, this phase expands the number of studied patients and evaluates the comparative effectiveness of the drug against existing treatments (or placebo, if applicable). At this stage, potential adverse effects and contraindications are also mapped.

“The process of creating a new drug can last more than 10 years. There are several steps, from basic research to clinical trials, to get all the guarantees of safety and efficacy of the treatment in question, and then take it to patients”, says Kratz.

Chagas and leishmaniasis: silencing and stigma

More than 100 years old, Chagas disease kills 14 thousand people per year in Latin America, more than any other parasitic disease. There are an estimated 6 million Trypanosoma cruzi-infected people in the region and another 70 million at risk of contracting the disease worldwide. However, less than 10% of patients are diagnosed and only 1% receive adequate treatment. A WHO report on NTDs, published in 2012, goes beyond epidemiological statistics and points out that premature Chagas deaths lead to a loss of about 800 business days / year and a R$1.2 billion in wasted productivity due to heart complications and other lesions resulting from the disease.

Leishmaniasis follow a similar path. Caused by more than 20 species of the Leishmania protozoan transmitted to humans by 30 other sand fly mosquito variations, they still have an uncertain incidence and lethality rate due to lack of reporting in more remote areas. In its visceral form, it can lead to death in 90% of cases. In the cutaneous and mucocutaneous manifestations, it leaves lesions that drive the infected away from their productive and social lives.

“Despite the significant global burden, these diseases have been ignored by the pharmaceutical industry, which has never seen them as a business itself. As a result, there still lacks therapeutic alternatives that could improve the quality of life of people with these diseases, laments Kratz. Until 2016, Brazil was one of the 12 largest global research funders for neglected diseases. The recent Global Innovation Funding for Neglected Diseases (G-Finder2) report, however, showed a 42% retraction in the sector over the following year. This is a setback for the drug discovery industry which, because it takes time, needs robust and continuous investment.

The document also revealed that less than 5% of funding was invested in the group of extremely neglected diseases, namely sleeping sickness, visceral leishmaniasis and Chagas disease, although more than 500 million people are threatened by these three parasitic diseases. Neglected diseases are a global public health problem, but pharmaceutical industry R&D is almost always profit-driven, with the private industry sector focusing on global diseases for which medicines can be produced and marketed for profit. With low purchasing power and no political influence, poorer patients and healthcare systems cannot generate the financial return required by most profit-driven companies.

In recent years there have been significant advances and collaborations in the area that have helped populate the current development pipeline. To maximize the chances of neglected patients accessing new drugs, it is crucial that all agents involved in R&D keep their efforts focused on understanding diseases and improving research strategies, without forgetting the importance of valuing science and promoting a favorable environment for research. Brazil has great potential for discovering new drugs against neglected diseases, and funding from Fapesp and partners helps to bridge this gap.

(With information from the Drugs for Neglected Disease Initiative (DNDi)

…