Does higher temperature reduce the incidence and mortality by COVID-19? What about the Tropics?

Would higher temperatures be protective for COVID-19 transmission? A study examined the connections between climate and severity of the disease

10/11/2020

If the results are confirmed, this is an important finding by showing that in a variety of configurations, there are strong evidences of an increase in COVID-19 severity with low temperatures and high humidity

Winter is rapidly approaching in the northern hemisphere, and researchers warn that outbreaks of COVID-19 tend to get worse, especially in regions that do not have the spread of the virus under control. Infections caused by many respiratory viruses, including Influenza and some coronaviruses, increase during the winter and decrease in the summer. Researchers say it is too early to say whether SARS-CoV-2 will become a seasonal virus. But growing evidence suggests that a small seasonal effect will likely contribute to larger outbreaks in winter, based on what is known about how the virus spreads and how people behave in the colder months.

A pre-print, a non-peer-reviewed article published in medRxiv entitled “Effects of environmental factors on severity and mortality of COVID-19” examined the links between climate and severity of COVID-19 cases. According to the study, the severity of COVID-19 in Europe dropped significantly between March and May and the seasonality of the virus is the most likely explanation. According to the study, a mucosal and mucociliary barriers can significantly reduce the viral load and disease progression, and its inactivation by low air humidity in indoor environments can significantly contribute to the severity of the disease.

In order to assess the association of humidity and room temperature with the severity of COVID-19, the study analyzed individual data from 6,914 patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospitals in Bergamo (Italy), Barcelona (Spain), Coburg (Germany), Helsinki (Finland), Milan (Italy), Nottingham (UK), Warsaw (Poland) Zagreb (Croatia) and Zhejiang Province (China) since the beginning of the pandemic and compared with ambient temperatures and calculated indoor air humidity. In addition, it analyzed the severity information of COVID-19 from the COVID Symptom Study application, which is collecting information from 37,187 individuals in the United Kingdom.

If the same findings are repeated in other investigations, this represents an important result in showing that, in a variety of settings, there is strong evidence of an increase in the severity of COVID-19 at low temperature and humidity, and would be associated with the winter months of temperate climates, which is common to other respiratory infections such as seasonal flu. Asked if the incidence and mortality by COVID-19 would be lower in the tropics due to higher temperature, the first author, Domagoj Kifer, from the Department of Biophysics of the Faculty of Pharmacy and Biochemistry of the University of Zagreb, Croatia, relaxes by saying that he has never lived in the tropics, but is soon serious and says that there are no temperatures so cold in the tropics that need warming. On the other hand, in Croatia we have winter temperatures below 0°C. When the air temperature increases from 0°C to 20°C, the relative humidity would decrease from a maximum of 100% to 29%. Living in such a dry environment could reduce the functionality of the mucus. When we compared mortality in tropical countries, we found that it was always lower than in the northern hemisphere winter wave, he says. Still according to him, in relation to the effect of ambient temperature on the gravity of COVID-19, there is some certainty, but the size of this effect seems to be quite small compared to other factors. Therefore, according to the researcher, it is difficult to say anything about the effect of ambient temperature based on available data. Furthermore, the change in the average daily ambient temperature should be greater to make some effect – I do not think that if you experience such an effect in the tropics, he says.

Warm air and humidity

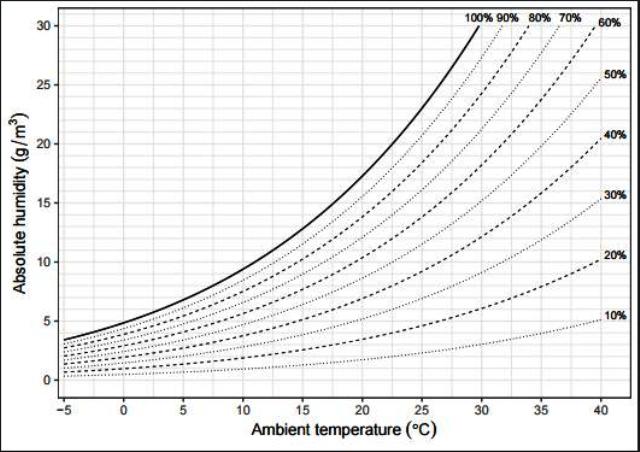

Hot air has greater humidity capacity than cold air. If the cold air (low humidity capacity) gets warm (higher humidity capacity), it becomes dry. Dry air makes mucus dryer.

Crédito: Domagoj Kifer

The horizontal axis (x) shows the ambiente temperature, while the vertical axis (y) shows the absolute humidity, i.e., the mass of water particles per volume of air. The curves show the relative humidity, the percentage of grams by the total of grams that could be contained in 1 cubic meter of air at a given temperature. By increasing the temperature, the same cubic meter of air may contain more grams of water.

If we consider 1 cubic meter of outdoor air, where it is at 0ºC with 100% relative humidity, you will have 5g of water; then, heat this air to 20ºC, where it will still contain 5g of water, but now you will have only 29% relative humidity, because 1 cubic meter of water at 20ºC supports up to 17.5g of water (estimated by the graph), resulting in 5g/m³ over 17.5g/m³, equals to 0.2857 or 28.57% (above 29%).

In other words, if you have hot air with 100% relative humidity, none of the water molecules can leave the mucus to the air (which would make the mucus drier); on the other hand, if you have cold air (at 10ºC) with 100% relative humidity (consider 10g/m³ as absolute humidity), and heat this air to a body temperature of 37ºC, it will still have about 10g/m³ of absolute humidity, but that would be approximately 20% of the relative humidity (estimated from the graph), which would allow the water particles in the mucus to be transported to the air, making the mucus drier. By exhaling the air, which will again become cold (external environment at 10ºC) – that air will contain more water than it can withstand at 10ºC, and the excess water will condense into small droplets and look like a fog – which is common during the winter in Croatia. This condensed water is lost from the mucus in our respiratory system, and because of this lost water, our mucus becomes drier.

Combination of climate and younger population

How to explain the difference between Africa and Latin America and why Africa has had fewer cases than other countries? Kifers reminds it would be wrong to compare the number of cases or the number of deaths, since the testing policies are probably very different between countries and continents. However, he admits that a very small number of people died in Africa, which in his understanding could be a combination of climate and younger population. Ourworldindata.org points to a small reduction in the lethality rate, however, the potential reason for this may be the change in testing policies in South Africa, as the number of tests increased about 2.5 times in mid-July (winter) compared to May (fall). There are many other effects that can also affect the mortality rate, besides temperature, admits Kifer.

Still exemplifying the tropics, according to ourworldindata.org, Australia took off in late winter and had a lethality rate of 3% in September (late winter in the southern hemisphere) and 1.5% in May (fall), although testing was more widespread in September. However, it is difficult to draw any conclusions from these figures, since it is not only a function of the weather effects, but of many others as well. Regarding the main difficulties in estimating the impact of climate on the dissemination of COVID-19, Kifer explains that it is impossible to estimate it because all other effects on dissemination cannot be kept constant, such as government decisions on isolation and social distancing, improvement and compliance with prevention protocols and environmental hygiene, among others.

Low temperatures decrease normal mucus clearing of infecting viruses in nasal airways

According to the study, very dry indoor environments created by air conditioning in hot countries (such as the southern United States) can also contribute to the severity of the disease. According to Kifer, dry cold air is actually more damaging to our mucosa than hot, dry air. However, in hot climates, this can be corrected by opening windows frequently, which would restore internal humidity. The publication also suggests that SARS-CoV-2 is more lethal in the winter because it is a seasonal virus. The mucus barrier is the first line of defense. We believe that due to the dry air (common in winter) the functionality of the mucus is reduced – what favors the virus’ seasonality”, he observes.

The study shows an association between temperature and the severity of symptoms, but does not show why this happens. Asked if low temperatures decrease the normal clearing of mucus from infectious viruses in our nasal airways, Kifer comments that although often considered a physical barrier, mucus is actually an active biological barrier that links viruses and bacteria to mucins, a group of highly glycosylated proteins that are secreted from our mucous barriers. Mucins mimic glycosylation of the cellular surface and by acting as a decoy to the viral lectins they trap the viral particles, which are then transported out of the airways by mucociliary elimination. However, this barrier only works if it is well hydrated to maintain its structural integrity and allow a constant flow of mucus that removes viruses and other pathogens from our airways. If exposed to dry air, these barriers dry up and cannot perform their protective functions, he adds.

When the outside temperature drops, we tend to heat that cold air when it reaches our homes. Warmer air has a higher humidity capacity compared to cold air and by increasing the air temperature we are reducing the relative humidity – we are drying out the air, which affects the function of the mucus. Although low temperatures do not directly decrease the protective function of mucus, they play some role in it due to the relatively low capacity of humidity, explains Kifer while adding that heating does not have to happen artificially through a heating system – when we breathe cold air, it will heat up inside us, then, by getting a higher capacity of humidity, the hot air will dry our mucus. In our study, we have not demonstrated why this happens, we are only suggesting it as a potential mechanism, he justifies.

If there is indeed a wave of infections, we may have a double blow of severe respiratory diseases. The second wave could be a consequence to the elimination of circulation restrictions – at least in Croatia and will probably influence the emergence of viruses this winter along with SARS-CoV-2. Fortunately, the same measures (i.e. social distancing, hygiene, etc.) protect us from all viruses at the same time, he concludes. But the fact is that any increase in severity and mortality would not only be a tragedy for those affected, but also represent an additional burden to our health systems, as new outbreaks and a potential second wave of COVID-19 infections in the coming months are almost inevitable.