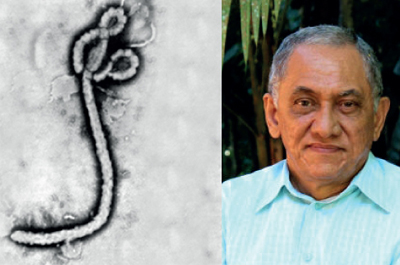

Ebola não deve se tornar uma epidemia mundialEbola should not become a world epidemic

O perigo é ele se estabelecer em área fora da zona endêmica, mas as medidas de contenção e proteção costumam ser eficientes e limitam a disseminação do vírusThe risk is the vírus establishing outside of the endemic zone, but the contention and protection measures are usually eficiente and limit the virus’ dissemination

17/06/2014

O perigo é ele se estabelecer em área fora da zona endêmica, mas as medidas de contenção e proteção costumam ser eficientes e limitam a disseminação do vírus

De acordo com a Organização Mundial da Saúde (OMS), a epidemia de ebola na África Ocidental está entre a mais assustadora já registrada desde quando o vírus foi identificado pela primeira vez, em 1970, no que hoje é a República Democrática do Congo. Dados atualizados pela OMS apontam que o surto já matou mais de 140 pessoas – a situação mais crítica encontra-se na Guiné, onde 129 pessoas já perderam a vida – e mais de 200 casos suspeitos foram registrados até agora. O surto é temível porque não há nenhum medicamento para tratar esta doença, cuja letalidade chega a algumas epidemias a mais de 80% dos casos. Mas isso pode mudar. De acordo com matéria publicada recentemente na mídia, um medicamento contra o ebola pode estar pronto para testes em humanos no próximo ano.

Dr. Pedro Vasconcelos, médico pesquisador do Instituto Evandro Chagas (IEC) e chefe da Seção de Arbovirologia e Febres Hemorrágicas, ratifica que não existe droga antiviral disponível atualmente para tratamento do ebola e de outros vírus que causam febres hemorrágicas, por exemplo, dengue, febre amarela etc. “Assim, a possibilidade de vir a ser administrada uma droga para o tratamento do ebola e outros vírus é promissora, embora deva ser lembrado que essas doenças são agudas e qualquer medicamento que venha ser utilizado deve ser aplicada nos primeiros dias da doença, o que limita muito o uso dela”, complementa. Para o especialista, de fato, o quadro clínico do ebola e outras viroses hemorrágicas evolui por no máximo 1 semana a 10 dias, e portanto o tratamento deve ser nos primeiros dias e nem sempre a suspeita do diagnóstico de ebola é fácil ou rapidamente realizado.

Sobre o ebola, Dr. Vasconcelos, que também é Coordenador do Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia para Febres Hemorrágicas Virais (INCT-FHV), ressalta a existência de mais de uma espécie deste vírus, todos restritos ao continente Africano. “O ebola é nativo da África, mas assim como há muitos vírus nativos das Américas (EEEV, WEEV, Mayaro e Oropouche) que não foram associados com transmissão fora do continente – não há transmissores eficientes ou que não tiveram chances de se tornar endêmicos – o mesmo ocorre com o ebola”, tranquiliza.

Outra causa de não expansão geográfica da transmissão do vírus é que os possíveis transmissores – ainda não confirmados, mas supostamente envolvidos nos casos iniciais –, os morcegos, são muito localizados e costumam ficar restritos às áreas onde vivem e a transmissão inter-humana perde força dos casos índices para os casos secundários e destes para os terciários, e assim o surto (ou epidemia) fica restrita e o número de casos limitados.

Epidemia mundial

De acordo com Dr. Vasconcelos, o ebola não pode se tornar uma epidemia mundial justamente porque a transmissão é muito restrita e área endêmica focal (na África) em áreas remotas. “A única possibilidade de ele vir a se tornar epidêmico como, por exemplo, a influenza, é se ocorrer adaptação do vírus no organismo humano e a transmissão possa ocorrer já não por contato com secreções/excreções orgânicas, mas por via respiratória. Aí sim ele poderia se tornar uma muito mais séria ameaça e causar pandemia”, ressalta.

Sobre a possibilidade do ebola se disseminar e do Brasil pode vir a ter a circulação desse vírus, o especialista alerta que o perigo é ele se estabelecer em área fora da zona endêmica, mas que é pouco provável, pois as medidas de contenção e proteção costumam ser eficientes e limitam a disseminação do vírus. “Ademais, a transmissão interpessoal para ocorrer é preciso que exista um contato intenso e com as secreções e/ou excreções do paciente”, lembra.

O contágio

A transmissão do caso índex em geral é desconhecido, mas nos casos secundários geralmente é pelo contato direto entre pessoas, principalmente pelas secreções dos pacientes em fase aguda da doença (período de viremia). Dr. Vasconcelos atenta que o uso de equipamentos de proteção individual (EPI’s) é recomendável. Além disso, nos casos suspeitos ou confirmados é mandatório o isolamento do paciente e uso de EPI’s para contenção da transmissão.

Uma vez contraído o vírus a letalidade é extremamente elevada. “Isso se deve ao comprometimento intenso e severo de múltiplos órgãos do organismo. Não há tratamento específico (antiviral) para tratar a febre hemorrágica por ebola. O tratamento é de suporte e sintomático, ou seja, para manter os sinais vitais e tratar os sintomas/sinais que costumam ocorrer nos casos da doença”, atenta o especialista ao lembrar que para prevenir à infecção as medidas seriam: evitar contato com os transmissores; não comer carne de animais selvagens; proteger-se ao manusear carcaças de animais silvestres, particularmente de primatas não humanos que ainda hoje é uma iguaria na África e tem sido vinculado ao início de surtos com a ingestão de carne de animais abatidos, ou encontrados doentes e mortos.

The risk is the vírus establishing outside of the endemic zone, but the contention and protection measures are usually eficiente and limit the virus’ dissemination

According to the World Health Organization, the ebola epidemic in West Africa is among the most frightening registered since the virus was identified for the first time in 1970, where currently is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Data updated by the WHO reads that over 140 people have died by the outbreak – Guinea has the most critical situation, with 129 dead – and over 200 suspicious cases were registered to the moment. The outbreak is fearful because there is no medication against the disease, whose lethality is over 80%. However, this can change. According to an article published in the media, a medication against the ebola virus could be ready for human tests next year.

Dr. Pedro Vasconcelos, researcher doctor from the Evandro Chagas Institute (ECI) and chief of the Arbovirology and Hemorrhagic Fevers, says there is no antiviral drug against the ebola or other viruses that cause hemorrhagic fevers, for example, dengue fever, yellow feer, etc. available at the moment “This way, the possibility to administer a drug for ebola treatment is promising, although we should keep in mind that these diseases are acute, and the any medication should be used in the first days of the disease, what limits its use”, complements. For the specialist, in fact, the clinical picture of the ebola and other hemorrhagic virus diseases evolves for 1 week to 10 days at most, and thus the treatment should be during the first days and the ebola’s diagnostic suspicion is not always easy or quickly done.

About the ebola, Dr. Vasconcelos, who is also Coordinator of the National Institute of Science and Technology of Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (NIST-VHF), stresses the existence of over once species of this virus, all restricted to the African continent. “Ebola is native from Africa, but as many viruses are native from the Americas (EEEV. WEEV, Mayaro and Oropouche) that were not associated to transmissions outside of the continent – there are no efficient transmitters or did not have the chance to become endemic – the same happens to the ebola”, he reassures.

Another reason for the virus not expanding geographically is that the possible transmitters – not yet confirmed, but supposedly involved in the initial cases -, bats, are very local and usually keep restricted to the areas where they live, and inter-human transmission looses power from the index cases to the secondary cases, and these to the tertiary cases, and this way the outbreak (or epidemic) keeps restricted and the number of cases limited.

World epidemic

According to Dr. Vasconcelos, the ebola will not become a world epidemic especially because transmission is very restricted and the focal endemic area are remote areas. “The only possibility of it becoming epidemic, for example, as the influenza, is if the virus adapts to the human organism, and the transmission is no longer by contact with organic secretions/excretions, but via respiratory ways. This way it could become a much more serious threat and cause a pandemic”, highlights.

Regarding the fact of the virus disseminating and circulating in Brazil, the expert alerts that the danger is the virus establishing outside of the endemic zone, but this is little likely to happen, because the contention and protection measures are usually efficient and limit the virus’ dissemination. “Moreover, in order to have interpersonal transmission, intense contact with the patient’s secretion/excretion must happen”, reminds.

The infection

The index case transmission is usually unknown, but the secondary cases happen usually between people, especially through the patient’s secretions during the acute phase of the disease (viremia period). Dr. Vasconcelos recommends the use of Individual Protection Equipment (IPE). Besides this, isolating the patient is mandatory whenever there is suspicion of confirmation of the disease in order to contain the transmission.

Once infected by the virus, lethality is extremely high. “This is due to the intense and severe impair of multiple organs. There is no specific treatment (antiviral) for the ebola’s hemorrhagic fever. The treatment is based on support and symptoms, i.e. in order to keep the vital signs and treat those symptoms usually associated with the disease”, warns the specialist while remembering that in order to prevent the infection, the measures are: avoid contact with the transmitters; do not eat wild animal meat; use protection whenever handling wild animal carcasses, especially non-human primates, which still are a delicacy in Africa and are related to outbreaks whenever sick or dead animals are eaten.…